Brushite stones are made of calcium and phosphate. Did you know that before you form calcium oxalate stones, they start as brushite crystals first?

This must be mind-blowing on your part!The following sections will explain why brushite crystals transform into calcium oxalate and vice versa. For now, let’s explain in detail what brushite stones really are.

What are Brushite Stones?

Brushite stones are whitish or beige and typically have large and pointy rod-shaped crystals. They somehow resemble a cabbage.

Brushite is a calcium phosphate crystal (calcium monohydrogen phosphate). It is similar to the initial layers of bone minerals. These stones are very rare; less than 1% of stone-formers have them.

When calcium is present in the urine, brushite is the first crystal to appear. It forms more readily than calcium oxalate or other calcium phosphate crystals. Sometime later, brushite can convert into either stone type.

However, there are times when brushite crystals don’t completely convert into another stone type. If your stone contains any trace of brushite, regardless of its percent, it is considered a brushite stone. This classification is essential because brushite stones are resistant to Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL) and pose a higher risk of kidney damage! We will give more details about this later.

Before we discuss why brushite crystals convert into other stone types (or not), let’s first discuss the causes of brushite stone formation.

What Causes Brushite Stones to Form?

The significant factors contributing to brushite stone formation are high urinary calcium (over 250 mg/L), low urinary citrate (below 320 mg/L), and elevated urine pH (6.5 to 6.8).

Metabolic issues (a.k.a. issues with your body converting food into energy) can also be involved. These include distal renal tubular acidosis (which results in alkaline urine) and primary hyperparathyroidism (which results in more urinary calcium). In a study of 82 brushite stone-formers, every patient had at least one abnormality in their 24-hour urine test. Many patients had multiple metabolic issues.

We have separate blogs about distal renal tubular acidosis and primary hyperparathyroidism. We recommend reading them to better understand how these conditions increase kidney stone risk.

Undergoing Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL) can also contribute to your increased risk of brushite stones. When shock waves are delivered at 18 to 24 kV (kilovolts) using a device called HM3 lithotriptor, blood flow to the kidneys is reduced. This shows the impaired function of the kidney’s small tubes. Other studies show that shock waves also damage the kidney’s papillae (tips of the kidney’s pyramid-like structures), which are essential in urine production. The damage in the kidney’s tissues impairs pH regulation, too. The most common result is an alkaline urine that sets up brushite stone formation.

Let’s dig deeper into the mechanism of how brushite crystals form.

The Mechanism: How Brushite Crystals Form

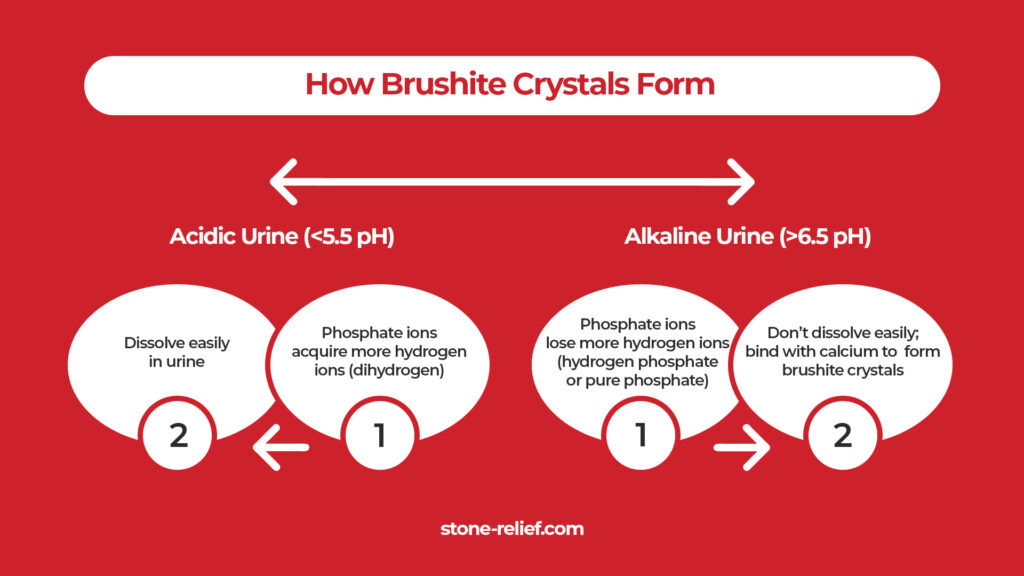

Urine pH highly influences brushite stone formation. In acidic urine conditions (around 5.5 pH), phosphate ions acquire more hydrogen ions. They become dihydrogen phosphate (one phosphate and two hydrogen ions), which dissolves easily. The more hydrogen ions there are, the easier they dissolve.

As urine pH rises (around 6.5 to 6.8), more phosphate ions convert into hydrogen phosphate (one phosphate and one hydrogen ion) and phosphate (no hydrogen ion). These two don’t easily dissolve. Makes sense! Anything compact is harder to break – just like your relationship with your best friend.

Thus, at urine pH levels around 6.5 to 6.8, there’s sufficient hydrogen phosphate available to combine with calcium ions, forming a brushite crystal. Here is a critical question: if brushite is a calcium phosphate crystal, why is it the first to form in the urine? This is compared to other calcium phosphate crystals, such as the most common hydroxyapatite (whitish or off-white) or the rare carbonate apatite (brownish-yellow to gray). The following section will give an answer.

Why Brushite Crystals Form First

Brushite stones form at lower concentrations of calcium and phosphate ions, compared to other calcium-based crystals. The reason is lower energy barrier for brushite, which allows it to form initial crystals more easily.

Suppose there’s around 2-6 mmol/L (or 80-240 mg/L) of calcium, 8-32 mmol/L (or 312-1248 mg/L) of phosphate, and 0.2-0.8 mmol/L (or 12-48 mg/L) of oxalates in the urine. Let’s say the temperature is around 37 degrees Celsius, and the urine pH is at 6.5-6.8. The supersaturation (excess amounts that don’t dissolve) of calcium-phosphate would be around 1.2, while 1.8 for calcium-oxalate. At this rate, brushite would start forming at around 1,400 minutes or nearly 24 hours.

Even with significant amounts of oxalates, phosphate would bind with calcium first in these conditions.

But isn’t calcium oxalate the most common kidney stone type? What specific conditions determine calcium oxalate then? The next section will explain.

Brushite Conversion into Calcium Oxalate

Again, brushite usually forms first. However, after some time, it converts into calcium-oxalate. How is that possible?

Given the same conditions above, brushite can convert into calcium-oxalate because a person’s urine pH isn’t constant. When urine pH drops to around 6.0 (the peak would be around 5.5), brushite stops growing, and calcium-oxalate thrives after 100 minutes. Since slightly acidic urine is no longer favorable for brushite, oxalate starts stealing calcium ions from brushite. That’s an opportunist robber right there! This explains why brushite seems to vanish in thin air.

Uric acid also plays a significant role here. Brushite starts forming in the urine solution at around 1400 minutes. However, something interesting happens when 0.05 mmol/L (8.406 mg/L) of uric acid is added to this solution. Brushite starts forming much earlier, around 900 minutes instead of 1400 minutes. This suggests that uric acid somehow accelerates the process of brushite crystallization.

Human urine typically contains 0.5 to 4 mmol/L (84.055 to 672.44 mg/L) of uric acid, which is too low to form uric acid stones. Uric acid levels typically associated with stone formation are generally above 800 mg per day in men and 750 mg per day in women.

With uric acid in the solution, calcium oxalate starts forming only 30 minutes after brushite does. This is much faster than when uric acid is not present.

This indicates that uric acid not only speeds up brushite formation but also the transition to calcium oxalate crystals.

When citrate is added at the same concentration of 0.05 mmol/L (9.606 mg/L), which is a small amount, brushite crystallization is delayed.

Instead of forming at the usual time, brushite starts crystallizing much later, after about 3000 minutes. This delay shows that citrate slows down the process of brushite crystal formation.

After brushite starts to form, calcium oxalate crystals typically follow. With citrate present, it stretches to about 200-240 minutes. This means that citrate delays brushite formation and slows down the transition to calcium oxalate crystals. So, just do the math. If you reach the daily recommendation of 640 mg for urinary citrate, stone formation will be nearly impossible. This is especially true if you drink enough water and urinate often.

Okay, if all these factors determine brushite conversion into calcium-oxalate, what about other calcium phosphate stones? Let’s take a look at it in the next section.

Brushite Conversion into Other Calcium Phosphate Types

First, let’s do a recap: For brushite to convert into calcium-oxalate, there need to be two things: (1) slightly acidic urine (6.0 pH or less) and (2) small amounts of uric acid. This is in addition to urinary calcium and oxalates.

If urine pH goes to 6.9 and above, this sets up the stage for other calcium-phosphate crystals to form. Again, these could be either hydroxyapatite (the most common) or carbonate apatite (the rarest).

Usually, hydroxyapatite (a mineral made up of the same component as bones) forms when the urine becomes alkaline. However, when there are more carbonate ions than phosphate ions in the urine, the carbonate ions (one carbon and three oxygen) can replace phosphate ions.

Isn’t that a long walkthrough of conversions? Let’s add one more link to this insane chain of conversions.

Did you know that calcium oxalate stone-formers can become full-blown brushite stone-formers? It’s like getting swallowed by a snake and returning to zero on a Snake and Ladders game. We’ll tackle this in the next section.

From Calcium Oxalate to Brushite Stones

In the same study involving 82 brushite stone-formers, 17% had previously formed calcium oxalate stones.

Research indicates a link between brushite stone disease and prior Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL) treatment. Some studies suggest that many individuals who form brushite stones initially developed routine calcium oxalate stones but sustained some kidney tissue damage from SWL. As mentioned earlier, this can disrupt urine pH balance, potentially alkalizing urine. Again, this can lead to brushite stone formation over time.Once you have formed full-blown brushite stones, is there any difference in how they should be treated compared to other kidney stone types? Read the next section to find out. (HINT: There’s a lot!)

Treatment Strategy for Brushite Stones

Brushite stones are very dense, more than 1000 HU (Hounsfiled units). This density is resistant to Shockwave Lithotripsy (SWL).

For this stone type, Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is your best bet for stones over 10 mm in diameter. However, it should be noted that many patients would require a secondary PCNL procedure to attain around 93% stone-free results.

Since brushite stones require more surgical procedures, they also pose more risks of kidney tissue injuries. Brushite stones have a high recurrence rate and are linked to large plugs in kidney tubes. All these factors indicate that brushite stones pose more risks of kidney damage than other stone types.

If there’s a way for you to skip surgery for brushite stones, would you take it?

True enough, brushite stones under 10 mm in diameter can pass naturally. While natural supplements like CLEANSE will not break dense stones apart, they can help pass such stones naturally.

But, if you want a more robust way to prevent higher kidney damage risks, prevention must be your primary goal. The following section will give you some practical strategies.

Preventing Brushite Stones

Aim for a daily urinary citrate output of around 640 mg to prevent brushite stones. This requires an intake of about 1,200 mg of citrate, preferably from natural dietary sources rather than synthetic supplements. Juicing up to two lemons daily can provide you with sufficient citrate.

Natural sources are more readily absorbed by the body and don’t have the drawbacks of synthetic citrate, which often comes from black mold. We have a separate blog on this topic, which you can access here.

If you have sensitivities to fresh lemons, consider using natural supplements instead. We are developing our own citrate product made from real citrus fruits, giving you a natural and effective option. We will update all our community members once it’s ready.In addition to citrate intake, maintaining proper hydration (like drinking enough water regularly) is crucial. This helps produce enough urine to flush out stone-forming elements. Kidney stones take some time to form. So, it’s best to flush them out before they can stick together.

Brushite crystals grow best at a urine pH of around 6.5 to 6.8. So, keeping your pH at around 6.0 to 6.5 is best. You can achieve this naturally through an animal-based diet. Also, there are readily available urine pH test strips that you can easily use to check your urine pH at home on the regular. Lastly, if you want more in-depth guidance on how to use all this information to your advantage, join our Coaching Program. We would be very honored to help you stop kidney stones and get your life back.

REFERENCE:

1. Brushite: Key to Calcium Stone Prevention

2. Brushite Stone Disease as a Consequence of Lithotripsy?

3. Risk Profile of Patients with Brushite Stone Disease and the Impact of Diet

Responses