There are a lot of opinions regarding how to consume calcium and oxalates to prevent kidney stone formation. Many studies suggest that eating foods with oxalates is okay as long as you consume a good amount of calcium in your diet because they will bind in the gut. However, this is not advisable to do. We’ll explain why in this article.

First, we have to consider two things: (1) the foods we eat break down at different rates, so we can’t ensure that if we eat foods with calcium and oxalates, these elements will bind in the gut as we wish. (2) The amounts of calcium and oxalates in our food are difficult to measure. Thus, we’ll never know whether we are taking them in the proper proportions.

Let’s look at the following points.

CALCIUM AND OXALATES ARE ABSORBED AT DIFFERENT RATES

There are two types of oxalates – soluble and insoluble. The stomach, intestines, and colon absorb soluble oxalates (unbound or free). On the other hand, insoluble oxalates are bound, so they are unavailable for absorption and are simply excreted in the feces. That said, when calcium binds with soluble oxalates in the gut, these oxalates will become insoluble and excreted in the feces.

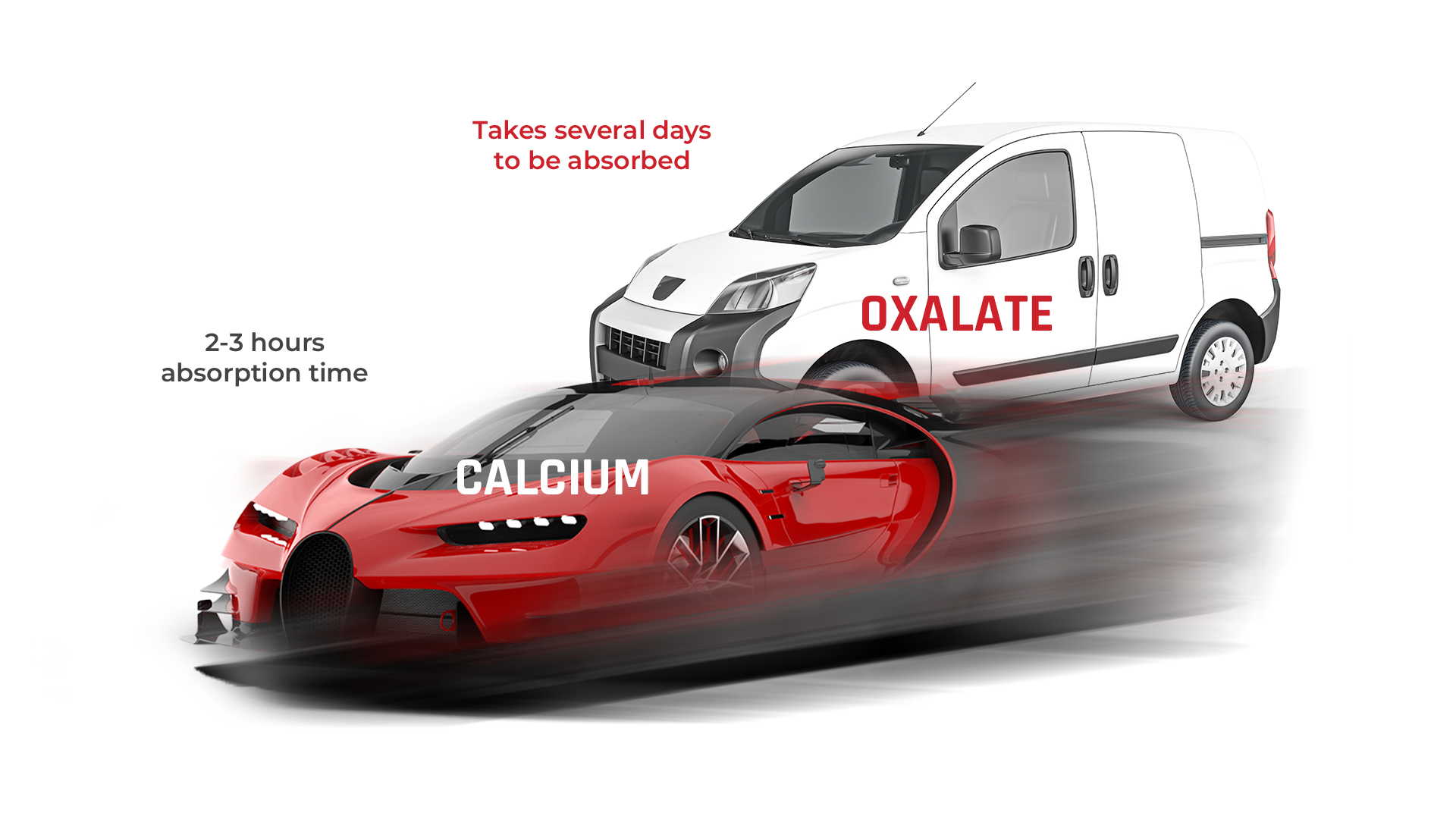

However, calcium and oxalates have different absorption rates. For instance, one study found that oxalates take several days to clear in the gut, whereas calcium takes only about two to three hours to be absorbed. Therefore, it is unreliable to assume that oxalates will perfectly bind with calcium in the gut.

How are Oxalate and Calcium Absorbed?

Oxalate absorption happens when transport proteins (from the SLC26 family) carry these elements across the cells. But passive absorption is also possible. Passive absorption occurs when there are “leaks” in the transport process within cells. Certain conditions that can lead to this are pancreatic deficiency, celiac disease (immune reaction to gluten), or Crohn’s disease (inflammatory bowel disease). Medical procedures like gastric bypass surgery for losing weight may also lead to passive absorption because it changes how the stomach and the small intestine handle food.

In addition, several bacteria, such as Oxalobacter formigenes, play some part. These bacteria degrade oxalates in the gut by feeding on oxalate for energy and cell carbon. So, the number of these diverse bacteria also affects how oxalates are managed in the intestinal tract.

All these can lead to oxalate absorption at different periods and amounts that are difficult to measure.

Meanwhile, the amount of calcium absorbed in the gut depends on dietary intake, bioavailability, and absorption time. Just like with oxalates, the stomach and the intestines absorb calcium. Calcium stays only about two to three hours in the gut because the Vitamin D receptors that transport calcium are very active. Additionally, studies show that calcium can be absorbed even faster if intake is higher.

CORRELATION BETWEEN CALCIUM AND OXALATES

Usually, substances are measured in milliosmoles (mmol), 1mmol is roughly around 40mg calcium and 88mg oxalates.

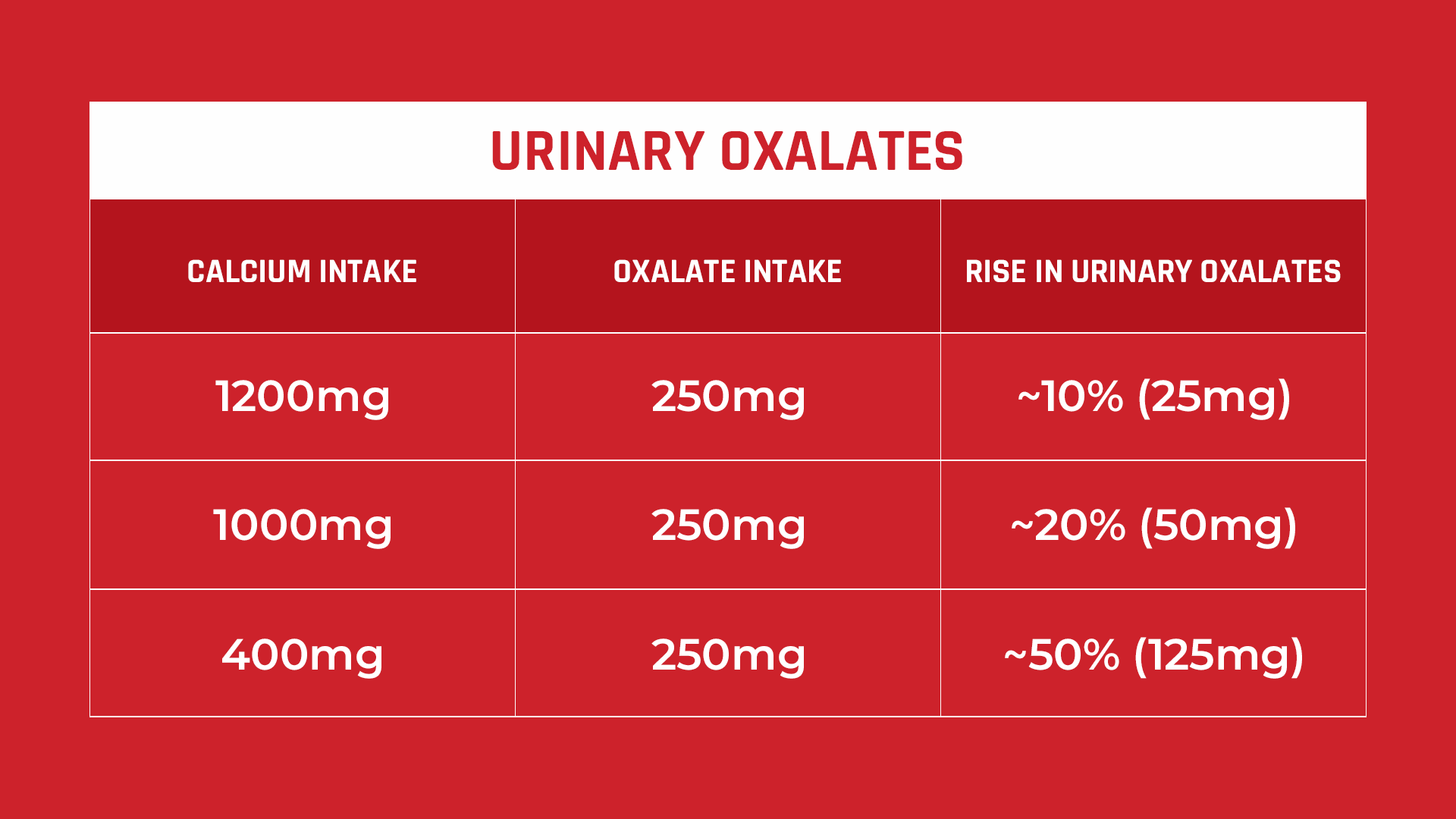

On average, 15–25 mmol (600-1000 mg/L) of calcium binds with 1–3 mmol (88-264 mg/L) of oxalate. However, urinary oxalate may increase around 2.7 mg for every 100 mg of oxalate consumed on 1000 mg of calcium. So if you take about 250 mg of oxalates with just 400 mg of calcium, your urinary oxalate levels will increase by more than 50%.

What if you eat cooked or raw spinach, which is super high in oxalate? Consuming a normal portion of spinach (50–100 g) will result in about ~500–1,000 mg of dietary oxalate. Imagine that!

Therefore, oxalate excretion of >25 mg/day is already a risk factor for kidney stones, and >40 mg/day can indicate primary or secondary hyperoxalurias. Primary hyperoxaluria refers to a rare genetic condition where there is an overproduction of oxalates, while secondary refers to a diet-based increase in oxalates.

PREVENTING CALCIUM OXALATE STONES

In order to prevent calcium oxalate stones, it’s important to control the concentrations of calcium and oxalates in your urine. Even if you consume both oxalate and calcium together in a meal, oxalate absorption will still increase due to the different rates at which they are absorbed in the gut. The most practical strategy is to eliminate oxalate-containing foods, since oxalates are simply waste products in the body. Meanwhile, dietary calcium intake should not be lowered. Calcium is essential in maintaining healthy bones, muscles, heart and nerves. So, calcium intake must be sufficient every day (~1,200 mg).

However, taking vitamin D supplements to get more calcium is not recommended, as some studies have shown that it can actually increase urinary calcium excretion and lead to recurring kidney stones.

Anyway, there’s still a lot more to know about kidney stone prevention. If you are serious in stopping kidney stones, jump into our Coaching Program and we will help you cut through the clutter and formulate an effective Prevention Plan.

Reference

- Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation and Their Association with Kidney Stone Disease: A Narrative Review

- Mechanisms of intestinal calcium absorption

- Contribution of Dietary Oxalate and Oxalate Precursors to Urinary Oxalate Excretion

- Role of dietary intake and intestinal absorption of oxalate in calcium stone formation

- Physiology of Intestinal Absorption and Secretion

- Net Intestinal Transport of Oxalate Reflects Passive Absorption and SLC26A6-mediated Secretion

- Vitamin D, Hypercalciuria and Kidney Stones

- Dietary oxalate and kidney stone formation

- Rapid Communication: relative effect of urinary calcium and oxalate on saturation of calcium oxalate

Responses