ARTICLE SHORTCUTS

- What is a Phosphate Leak?

- Phosphate Leak and Kidney Stones

- How Phosphate Leak Leads to Hypercalciuria

- Phosphate Leak Causes

- Manage Phosphate Leak

When you have a leaking faucet at home, you know it is a problem. Your water bill will be higher if not fixed in a short amount of time. In the same way, when phosphate leaks into your urine, it causes graver problems — calcium phosphate kidney stones.

You might not have heard of this, but there’s a condition where phosphate leaks into your urine. In fact, 20% of calcium stone formers with normal parathyroid function have this infamous condition. In the next section, we’ll give some background on what this condition is all about.

What is a Phosphate Leak?

A phosphate leak means that the kidneys are less able to reabsorb phosphate, causing excess levels in the urine, known as hyperphosphaturia.

The kidneys filter about 140 liters of water from blood plasma every day. Phosphate, measured as phosphorus, is about 1 mmol (millimole) per liter, around 32 mg/L or 3.2 mg/dL. However, 80-85% of this phosphate is reabsorbed by the kidneys, leaving only 15-20% (about 670-900 mg) to be excreted in the urine. This is typically observed in 24-hour urine collections.

In adults, phosphate balance is neutral; we can’t produce or destroy it, so what we absorb from our diet usually equals what we lose in urine and feces.

A typical result of a phosphate leak is a 25% or more urinary phosphate excretion.

Since calcium phosphate stones obviously require phosphate as a raw material, phosphate leak is risky. However, we should watch out for another risk factor connected to kidney stones if you have a phosphate leak. Curious? Read on.

Phosphate Leak and Kidney Stones

Aside from excess urinary phosphate, phosphate leaks also cause high urinary calcium levels. This is due to increased calcitriol (the active form of vitamin D) in the blood, which raises calcium excretion.

One study measured phosphate excretion in 207 people with kidney stones and normal parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels to confirm this connection. The results were compared with those of 105 people without stones.

The study showed that people with kidney stones tend to have lower phosphate thresholds, which means their kidneys don’t handle phosphate well.

Only 5% of the group without stones had a phosphate threshold below 0.63 mmol/L, while 19% of the kidney stone group did. Also, those with kidney stones had higher daily urinary calcium excretion, especially if their phosphate threshold was below 0.63 mmol/L. Interestingly, there were no differences in blood levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) or free (unbound) calcium between the groups.

But why is phosphate leak connected to calcium exactly? The following section will explain in detail.

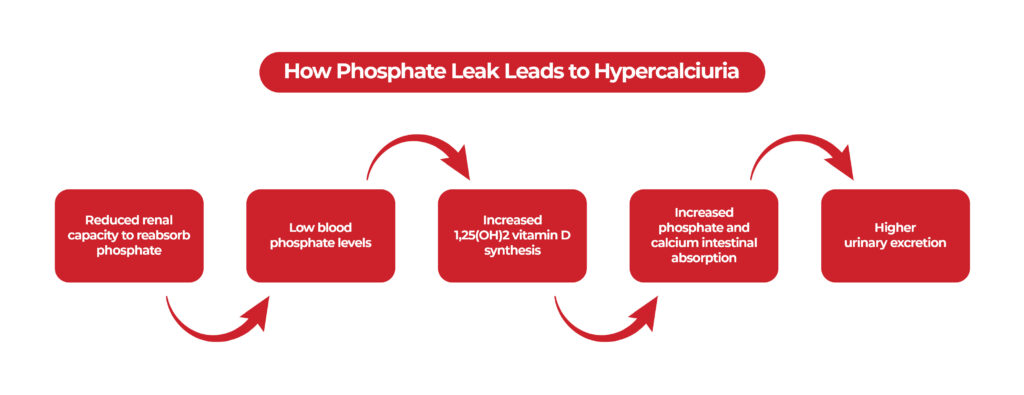

How Phosphate Leak Leads to Hypercalciuria

Typically, our body carefully manages phosphate and calcium levels through hormones like parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). These hormones team up to keep the right balance between calcium and phosphate.

There’s a seesaw effect between blood phosphate and calcium levels. Calcium levels tend to rise when phosphate levels drop; the reverse is true, too. This happens because PTH, which kicks in when calcium levels are low, helps boost calcium levels by releasing it from bones and enhancing calcium absorption from our gut. At the same time, PTH reduces phosphate reabsorption in the kidneys, which brings down blood phosphate levels.

When the kidneys struggle to reabsorb phosphate, it causes low phosphate levels (hypophosphatemia). This triggers increased production of active vitamin D, which then boosts the absorption of phosphate and calcium in the intestines, leading to higher calcium levels in the urine (hypercalciuria).

Now, one question stands – does phosphate leak always lead to hypercalciuria?

Not all the time. Hypercalciuria means urinary calcium of >300 mg in men and >250 mg in women. One study involving 100 adult kidney stone patients who consistently had hypercalciuria checked this connection. According to the researchers, only 9% of the patients had evidence of a phosphate leak. Their urine calcium levels weren’t significantly different from those without a phosphate leak. Thus, phosphate leak is uncommon among patients with excess urinary calcium and doesn’t seem to lead to higher calcium loss in urine.

If a phosphate leak proves to be the chink in your kidney stone escape plan, how do you tackle it? The next chapter will delve into its potential causes that require your immediate attention.

Phosphate Leak Causes

The reason why some stone-formers get phosphate leak remains unknown. None of the patients had a history of rickets (a condition that affects bone development in children), and there were no signs suggesting genetic issues like those seen in certain types of rickets. The clinical signs also differed from those found in another condition called oncogenic hypophosphatemic osteomalacia (caused by a specific kind of tumor).

Although a rare mutation in the CLCN5 gene (which helps regulate ion balance) has been reported in one patient with hypercalciuria, it’s not a common finding among stone formers.

Though high PTH levels commonly result in higher urinary phosphate, the case differed in stone-formers with excess urinary phosphate. Numerous studies reported that these patients usually have normal PTH and free calcium levels.

When the body doesn’t have enough blood phosphate, the kidneys tend to reabsorb more phosphate and vitamin D. Interestingly, patients eating a low-phosphate diet don’t seem to improve phosphate leak issues. This doesn’t really change PTH levels or calcium levels much, either.

So, it is safe to say that scientists still don’t fully understand how the kidneys reabsorb phosphate without the involvement of PTH. High calcium levels in urine can occur in both a phosphate-deprived diet and cases of renal phosphate leak.

But, we have some hypotheses on this issue.

Phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D have deep connections to each other. Our bones are primarily made up of phosphate and calcium (hydroxyapatite). And calcitriol, the active form of Vitamin D, transports calcium throughout the body. These three are like loving triplets that cannot be separated from each other.

Chronic deficiencies in your dietary intake of these three essential nutrients may contribute to a phosphate leak. Plus, if you are taking synthetic supplements that are putting additional strain on your kidneys, you may also be harming your kidney function in time.

These are only hypotheses, but since phosphate leak isn’t genetic, some dietary or lifestyle factors surely lead to it.

Anyway, if you already have a phosphate leak, can you fix or manage it? Absolutely! We’ll share some strategies for doing so in the next chapter.

Manage Phosphate Leak

Unlike your broken faucet at home, there’s no evidence that a phosphate leak is fixable. However, it’s totally manageable.

Managing a phosphate leak starts with addressing any underlying causes. If you can pinpoint the underlying cause, targeted treatments will be easier.

If the underlying cause is unknown, dietary adjustments are your best bet. It is essential to ensure that your intake of phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D through animal-based foods meets the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA).

Here are the RDAs for these three nutrients in adults per day:

- Calcium – around 1200 mg

- Vitamin D – around 600 IU (International Units)

- Phosphate – around 700 mg

Phosphate is generally abundant in the diet, and deficiencies are rare in healthy individuals with normal kidney function. However, monitoring your phosphate intake is necessary if you are experiencing a phosphate leak. Our Coaching Program will provide effective strategies for doing this.

For vitamin D, spending some time in sunlight, along with a proper diet, is best to boost its levels. We discourage synthetic supplements because the body doesn’t utilize synthetics efficiently. They end up as waste products, potentially leading to deficiency in the long run. Plus, synthetic drugs strain the kidneys.

It is essential to know that calcium is not the enemy. Whether or not a phosphate leak increases your urinary calcium levels is not the issue. Not even phosphate is the bad guy. Both calcium and phosphate are important electrolytes (electrically charged elements). If these two are not the enemies, then what is?

Alkaline urine. Alkaline urine (over 7.0 pH) is the mastermind of calcium phosphate stone formation. So, neutralizing urine pH is a crucial strategy. Again, the key here is eating animal-based diets because plant-based diets are generally alkaline in nature.

We know that navigating this kidney stone diet expedition can be like sailing through a thunderstorm – close to impossible. However, if a guide is helping you plot the course through the waves, it’ll surely be easier and doable. So, we’ll never get tired of inviting you to join our Coaching Program. This isn’t sales talk; this is your compass out of your kidney stone trouble.

REFERENCE

Responses