Whether you’re new to passing kidney stones or have passed them for years, kidney stones can be tricky. And, when it comes to knowing if you have truly, finally passed that agonizing kidney stone, sometimes you just don’t know. Well today, it’s out goal to try and clear up as much of the uncertainty as we can by introducing you to the three ways that a kidney stone can pass. Let’s dive in.

THE WHOLE STONE

The most obvious way you know you passed your stone is if it pops out of your urethra whole. But, kidney stones take on all different shapes and features. So, how do I know if I got it all? Well, even though they may look horrific and complicated, there are only a few distinct ways that stones form that we can use to help us determine if all of it has passed.

The top two ways that stones form in our bodies are either free-floating in the kidney calyx or pelvis or attaching themselves to the wall of the kidney. Stones that form free-floating in the kidney are spherical and sometimes have little areas of budding where new parts of the stone are emerging (like calcium oxalate monohydrates stones). These stones are very dense and rarely break apart while passing. So, if you pass a spherical and dark stone, it’s likely the entire stone, and you’re out of the woods.

However, when it comes to stones that form on the walls of the kidney, this is where things can get a little tricker. Kidney stones that form on the walls of kidneys tend to be less dense (calcium oxalate dihydrate, uric acid, and cystine). So, if you form stones like these, you can still end up passing your stone whole. But, there is a possibility that it will pass in another form.

The profession refers to these two other forms, either as “gravel” or “sand.” The names describe what you’re seeing. But let’s discuss gravel first.

GRAVEL

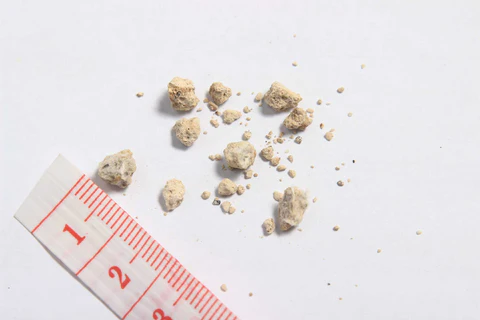

Gravel is smaller pieces of your larger kidney stone that have broken off while your stone is passing. As we mentioned above, this is less likely to happen if you form more dense kidney stones (like calcium oxalate monohydrate stones). However, if you form the less dense kidney stones (like calcium oxalate dihydrate, uric acid, and cystine stones), these stones tend to break apart while passing.

Less dense kidney stones can completely break apart and pass as gravel, with multiple smaller pieces of the stone exiting our system. Or, just a single or a few pieces can detach and leave a more significant chunk of the original stone left intact to pass. There are many factors that can influence this.

Primarily it will be the internal morphology of the stone and its density. But, we can influence these stones with supplements like CLEANSE to help break them apart. Just note that because you pass a piece of gravel, it does not mean that your entire stone will pass in this state. In most instances, if stones start to pass as gravel, you’ll get a few pieces and still have a more significant remaining chunk of the stone to pass.

You will know when you are passing gravel when you either start to see and or feel little pieces or specks of stone in your toilets. Sizes of gravel vary widely. In most instances, you will feel gravel as it exits your urethra. There is no pain. But, you’ll feel a little shock or jolt as it exits your urethra.

SAND

Sand is the next state in which kidney stones can pass. And, just like it sounds, this is when a kidney stone breaks down to very fine particles like sand. Depending on the stone type, some sand fragments can resemble tiny rice grains.

Unless you’re straining your urine (which we highly recommend), you will likely not see these sand-like particles as they pass. Instead, you will feel a hot/burning sensation while urinating. This sensation is due to these fine particles cutting your urethra as they exit. There’s no pain here and no damage being done. It’s just irritation as these particles pass, making tiny cuts.

Unlike stones that will pass as gravel, when you start to see sand in your strainer (or feel that hot/burning sensation), it’s likely that the rest of your stone will pass in this state. There will be people who get sand, gravel and pass a big chunk of their stone and every other scenario in-between. But, for most of us, stones will pass in one of these three formats.

POST PASSAGE

Regardless of the state that your stone ends up passing, it is important to try and capture as much of the kidney stone as you can. Kidney stone morphology (how a stone forms) can unlock the reasons as to why your kidney stones are forming. Take what you capture to your Urologist for analysis. Almost all kidney stones formed in the United States can be prevented with simple dietary/lifestyle changes and potentially with the help of select supplementation.

Now that you’re done passing this kidney stone, your urinary tract and kidneys are likely going to be sore for 1-2 weeks. All that pain you went through trying to pass that kidney stone has wreaked havoc on your urinary tract, and healing is slow. So, you will likely want to take Tylenol to help manage this soreness. Another key to your recovery is staying hydrated.

Your goal should be to get into a routine where you are consuming 64-96 oz (2-3L) per day. This routine will not only help you feel better faster, but it will help with the prevention of new kidney stones as well.

Responses